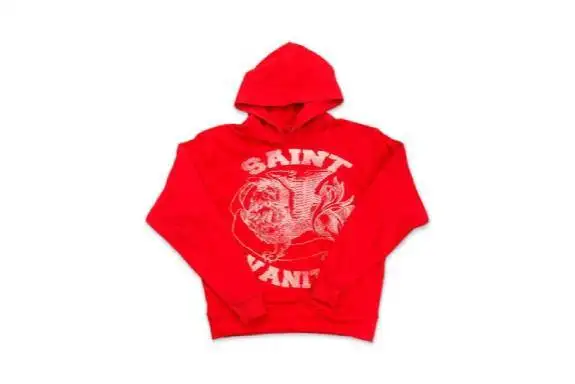

Saint Vanity | Saint Vanity Shirt | United States Store 2025

In a world that celebrates both humility and self-expression, the idea of “Saint Vanity” feels like a contradiction. Saints are seen as selfless, humble, and devoted to higher purposes—while vanity is often dismissed as shallow, prideful, and egocentric.

But what happens when these two seemingly opposite forces collide? Can someone do good while still caring deeply about how they are seen? Can virtue and image live side by side?

The concept of Saint Vanity opens a conversation about our motivations, our desire for recognition, and the way goodness is portrayed in both history and modern culture.

What Is Vanity, Really?

Traditionally, vanity is seen as an excessive concern with appearance or admiration. In religious teachings, it's often considered a sin—especially in Christianity, where it's tied to pride and self-idolatry. In Buddhist philosophy, it’s a distraction from enlightenment and the dissolution of ego.

But vanity isn't always purely negative. It can drive us to present ourselves well, to improve, and to connect with others. In fact, a small dose of vanity might even support morality when it inspires us to live up to a positive image.

This is where the idea of Saint Vanity begins: not as a fall from grace, but as a reflection of the human desire to be good—and to be seen as good.

Historical Saints and the Spotlight

Many of the saints we admire today were not only holy in life but carefully portrayed in death. Their stories were documented, their relics displayed, their images painted in gold and marble. Their goodness was not just practiced—it was seen.

While their virtues were genuine, they also became symbols. Their names were etched in history, not just for their sacrifice but for how they were remembered. In this sense, even saints were subject to the machinery of image and admiration.

Was this vanity? Or was it a necessary part of inspiring others?

In some cases, saints embraced their visibility to spread a message. They became icons—literally and metaphorically—whose image helped fuel movements of compassion, justice, and faith.

Saint Vanity in the Digital Age

Today, sainthood isn’t only found in religious figures. Activists, influencers, philanthropists, and even everyday people take on saint-like roles online—speaking out, helping others, advocating for change.

But many also curate their image, filter their photos, and track their likes.

Is this vanity? Or is it a new form of moral communication?

The line is blurry. A person who donates to charity and posts about it may be seeking praise—but also inspiring others. Someone who lives simply and shares their journey on social media may attract followers—but also raise awareness about sustainability or minimalism.

The modern saint often comes with a brand. And with that brand comes a mixture of virtue and vanity—wrapped in a single, very human package.

When Vanity Serves a Purpose

Vanity becomes problematic when it overshadows purpose. But when it supports or amplifies a mission, it can be powerful.

Public figures often use their influence to promote good causes. Their fame may come from vanity or style—but the outcome is still beneficial. If someone plants trees to be praised, the trees still grow. If someone feeds the poor for attention, the hungry are still fed.

Intent matters, but so do results. Sometimes, the desire to be admired pushes people to do admirable things.

This doesn’t excuse insincerity—but it acknowledges that human motives are rarely pure, and that complex motivations can still lead to meaningful impact.

The Inner Saint vs. The Inner Mirror

At the heart of Saint Vanity is a personal struggle: the desire to be genuinely good versus the desire to be seen as good. Most of us wrestle with this balance.

Do we volunteer because we care—or because we want recognition? Do we apologize because we regret—or because we want to look kind? These questions don’t always have clear answers.

But becoming aware of this tension can help us grow. It encourages us to examine our intentions while still appreciating the good that comes from our actions.

Conclusion: Embracing Saint Vanity

Saint Vanity is not a flaw—it’s a reflection of our humanity. It reminds us that even in our pursuit of goodness, ego plays a role. And that’s okay.

Rather than pretend we are entirely selfless, we can accept that part of doing good often involves being seen. What matters is not denying the mirror, but not getting lost in it either.

The saint and the vain person both live within us. The challenge is to let one inspire action—and keep the other in check.

- AI

- Vitamins

- Health

- Admin/office jobs

- News

- Art

- Causes

- Crafts

- Dance

- Drinks

- Film

- Fitness

- Food

- Jogos

- Gardening

- Health

- Início

- Literature

- Music

- Networking

- Outro

- Party

- Religion

- Shopping

- Sports

- Theater

- Wellness